Advertisement

Supported by

Experts Urge Strict Workplace Air Quality Standards, in Wake of Pandemic

The researchers issued a call to action to improve indoor air quality as a safeguard against the spread of contagions like the coronavirus.

Clean water in 1842, food safety in 1906, a ban on lead-based paint in 1971. These sweeping public health reforms transformed not just our environment but expectations for what governments can do.

Now it’s time to do the same for indoor air quality, according to a group of 39 scientists. In a manifesto of sorts published on Thursday in the journal Science, the researchers called for a “paradigm shift” in how citizens and government officials think about the quality of the air we breathe indoors.

The timing of the scientists’ call to action coincides with the nation’s large-scale reopening as coronavirus cases steeply decline: Americans are anxiously facing a return to offices, schools, restaurants and theaters — exactly the type of crowded indoor spaces in which the coronavirus is thought to thrive.

There is little doubt now that the coronavirus can linger in the air indoors, floating far beyond the recommended six feet of distance, the experts declared. The accumulating research puts the onus on policymakers and building engineers to provide clean air in public buildings and to minimize the risk of respiratory infections, they said.

“We expect to have clean water from the taps,” said Lidia Morawska, the group’s leader and an aerosol physicist at Queensland University of Technology in Australia. “We expect to have clean, safe food when we buy it in the supermarket. In the same way, we should expect clean air in our buildings and any shared spaces.”

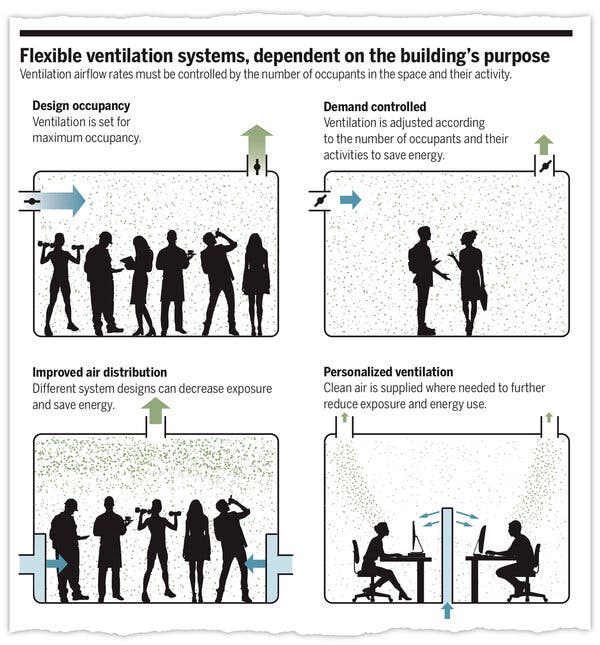

Meeting the group’s recommendations would require new workplace standards for air quality, but the scientists maintained that the remedies do not have to be onerous. Air quality in buildings can be improved with a few simple fixes, they said: adding filters to existing ventilation systems, using portable air cleaners and ultraviolet lights — or even just opening the windows where possible.

Dr. Morawska led a group of 239 scientists who last year called on the World Health Organization to acknowledge that the coronavirus can spread in tiny droplets, or aerosols, that drift through the air. The W.H.O. had insisted that the virus spreads only in larger, heavier droplets and by touching contaminated surfaces, contradicting its own 2014 rule to assume all new viruses are airborne.

The W.H.O. conceded on July 9 that transmission of the virus by aerosols could be responsible for “outbreaks of Covid-19 reported in some closed settings, such as restaurants, nightclubs, places of worship or places of work where people may be shouting, talking or singing,” but only at short range.

The pressure to act on preventing airborne spread has recently been escalating. In February, more than a dozen experts petitioned the Biden administration to update workplace standards for high-risk settings like meatpacking plants and prisons, where Covid outbreaks have been rampant.

Last month, a separate group of scientists detailed 10 lines of evidence that support the importance of airborne transmission indoors.

On April 30, the W.H.O. inched forward and allowed that in poorly ventilated spaces, aerosols “may remain suspended in the air or travel farther than 1 meter (long-range).” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which had also been slow to update its guidelines, recognized last week that the virus can be inhaled indoors, even when a person is more than six feet away from an infected individual.

“They have ended up in a much better, more scientifically defensible place,” said Linsey Marr, an expert in airborne viruses at Virginia Tech, and a signatory to the letter.

“It would be helpful if they were to undertake a public service messaging campaign to publicize this change more broadly,” especially in parts of the world where the virus is surging, she said. For example, in some East Asian countries, stacked toilet systems could transport the virus between floors of a multistory building, she noted.

More research is also needed on how the virus moves indoors. Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory modeled the flow of aerosol-size particles after a person has had a five-minute coughing bout in one room of a three-room office with a central ventilation system. Clean outdoor air and air filters both cut down the flow of particles in that room, the scientists reported in April.

But rapid air exchanges — more than 12 in an hour — can propel particles into connected rooms, much as secondhand smoke can waft into lower levels or nearby rooms.

“For the source room, clearly more ventilation is a good thing,” said Leonard Pease, a chemical engineer and lead author of the study. “But that air goes somewhere. Maybe more ventilation is not always the solution.”

In the United States, the C.D.C.’s concession may prompt the Occupational Safety and Health Association to change its regulations on air quality. Air is harder to contain and clean than food or water. But OSHA already mandates air-quality standards for certain chemicals. Its guidance for Covid does not require improvements to ventilation, except for health care settings.

“Ventilation is really built into the approach that OSHA takes to all airborne hazards,” said Peg Seminario, who served as director of occupational safety and health for the A.F.L.-C.I.O. from 1990 until her retirement in 2019. “With Covid being recognized as an airborne hazard, those approaches should apply.”

In January, President Biden directed OSHA to issue emergency temporary guidelines for Covid by March 15. But OSHA missed the deadline: Its draft is reportedly being reviewed by the White House’s regulatory office.

In the meantime, businesses can do as much or as little as they wish to protect their workers. Citing concerns of continued shortages of protective gear, the American Hospital Association, an industry trade group, endorsed N95 respirators for health care workers only during medical procedures known to produce aerosols, or if they have close contact with an infected patient. Those are the same guidelines the W.H.O. and the C.D.C. offered early in the pandemic. Face masks and plexiglass barriers would protect the rest, the association said in March in a statement to the House Committee on Education and Labor.

“They’re still stuck in the old paradigm, they have not accepted the fact that talking and coughing often generate more aerosols than do these so-called aerosol-generating procedures,” Dr. Marr said of the hospital group.

“We know that Plexiglas barriers do not work,” she said, and may in fact increase the risk, perhaps because they inhibit proper airflow in a room.

The improvements do not have to be expensive: In-room air filters are reasonably priced at less than 50 cents per square foot, although a shortage of supply has raised prices, said William Bahnfleth, professor of architectural engineering at Penn State University, and head of the Epidemic Task Force at Ashrae (the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers), which sets standards for such devices. UV lights that are incorporated into a building’s ventilation system can cost up to roughly $ 1 per square foot; those installed room by room perform better but could be 10 times as expensive, he said.

If OSHA rules do change, demand could inspire innovation and slash prices. There is precedent to believe that may happen, according to David Michaels, a professor at George Washington University who served as OSHA director under President Barack Obama.

When OSHA moved to control exposure to a carcinogen called vinyl chloride, the building block of vinyl, the plastics industry warned it would threaten 2.1 million jobs. In fact, within months, companies “actually saved money and not a single job was lost,” Dr. Michaels recalled.

In any case, absent employees and health care costs can prove to be more costly than updates to ventilation systems, the experts said. Better ventilation will help thwart not just the coronavirus, but other respiratory viruses that cause influenza and common colds, as well as pollutants.

Before people realized the importance of clean water, cholera and other waterborne pathogens claimed millions of lives worldwide every year.

“We live with colds and flus and just accept them as a way of life,” Dr. Marr said. “Maybe we don’t really have to.”

Advertisement