Why aren’t patients being told truth about electric shock therapy? Leaflets on the treatment contain at least one inaccurate statement about safety and effectiveness, investigation shows

Jacqui Quibbell has suffered from ‘crippling periods of depression and suicidal thoughts’ for all her adult life.

In 2003, her doctors suggested Jacqui underwent electro-convulsive therapy (ECT).

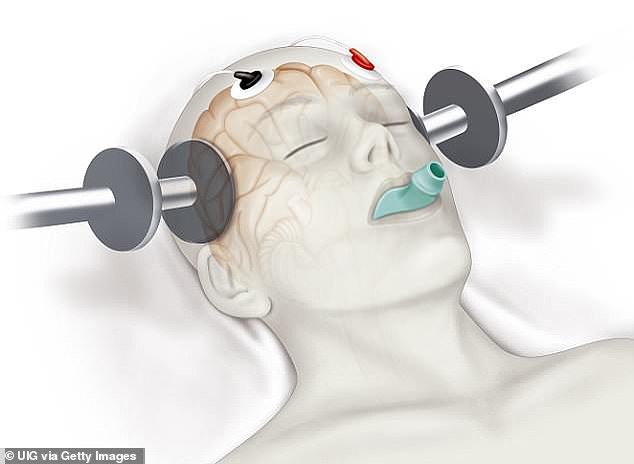

This involves attaching electrodes to the patient’s head and, under general anaesthetic, passing electric shocks through their brain — which is said to ‘rewire’ it.

‘I didn’t know much about ECT, I didn’t have Google then,’ says Jacqui, 57.

‘I started suffering memory loss during the treatment and by the time it finished, my short-term memory had disappeared completely and has never come back. I can’t recognise faces, even of people I know really well.’

Aged 39 at the time, she says there was ‘no way’ she could go back to work: ‘I had to give up a career I loved [as a senior local authority housing officer] and I’ve never worked since.

Her doctors suggested Jacqui underwent electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). This involves attaching electrodes to the patient’s head and, under general anaesthetic, passing electric shocks through their brain — which is said to ‘rewire’ it . The therapy is depicted above

‘ECT is archaic and barbaric,’ she adds. ‘It’s given to people in the most vulnerable circumstances when they’re not able to understand what they are consenting to.’

Jacqui’s experience is backed up by the startling results of a Freedom of Information request to hospital trusts for a copy of their ECT patient information leaflet.

This audit, published exclusively in the Mail, revealed that the leaflets — including one produced by the Royal College of Psychiatrists — contained at least one inaccurate statement about the safety and effectiveness of ECT, such as there being no risk of long-term memory loss.

As a result, patients were not able to give fully informed consent to the controversial treatment, the researchers behind the audit say in their report, published in the journal Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry.

ECT is approved on the NHS as a treatment for ‘depressive illness, schizophrenia, catatonia and mania’.

Psychiatrists maintain it lifts depression and saves the lives of people who might otherwise have committed suicide, by ‘resetting’ brain pathways (in ways still yet to be explained).

Some of the leaflets said the therapy carries little risk of memory loss, despite numerous reports otherwise — and the mental health charity Mind points out that ‘many people’ experience this, and sometimes it can be permanent

Under guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), last updated in 2009, the therapy should be used ‘only to achieve rapid and short-term improvement of severe symptoms after an adequate trial of other treatment options has proven ineffective and/or when the condition is considered to be potentially life-threatening’.

Particular caution is urged for its use in young people.

About 2,500 patients a year in England and Wales undergo ECT, which may involve between ten and 30 shocks to the brain administered days or weeks apart.

The audit, published today, showed that more than half of the trusts (51 were contacted, 36 responded) used leaflets with seven or more inaccurate statements, and failed to provide a full picture of the risks. For instance, they wrongly claimed that ECT could correct brain function abnormality — John Read, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of East London, who led the audit, says no research has shown this.

Some of the leaflets said the therapy carries little risk of memory loss, despite numerous reports otherwise — and the mental health charity Mind points out that ‘many people’ experience this, and sometimes it can be permanent.

Many also fail to mention that ECT should only be used when talking therapies have failed, as a last-resort treatment, as in the NICE guidelines.

Professor Read adds that the majority of patients given it are women aged over 60. ‘I think that is probably because they are less likely to have anyone to speak up for them and question why it’s being done, when it provides no long-term benefit and involves real risks of memory loss,’ he says.

What frustrates campaigners and researchers is that in 2003 NICE warned that information given to patients undergoing ECT was inadequate and said a national evidence-based leaflet should be produced.

But Professor Read says: ‘This was never done.’

He adds that in some leaflets, ECT is described as like dental anaesthetic – ‘which it isn’t – first of all it’s a general anaesthetic, not an injection, and patients are going to have at least ten of them which carry risks of their own’.

None of them spell out the fact there are no long-term benefits from ECT. About half of the leaflets don’t mention their right to ‘a legal advocate, that is someone to inform patients of their rights and support them in legal hearings’.

Jacqui, who lives in Milford, Derbyshire, says her own experience clearly bears out the need for an independent advocate.

‘Having read through my medical records, I apparently signed a form prior to each session. But when you’re in a state of acute depression, you are not in the best position to make a judgment about treatment.’

Jacqui is now part of a group legal action being co-ordinated by Freeths solicitors in Nottingham for people who claim they never gave informed consent to ECT and are seeking compensation for the brain damage they say they suffered.

Freeths solicitor Phillip McGough says they already have 12 complainants — one of their newest cases is ‘Chloe’, a 20-year-old from Newcastle who had a breakdown at 15 and was diagnosed by a psychiatrist with depression.

Aged just 17, she was referred for 26 sessions of ECT in 2018 which she says have caused epilepsy and permanent memory loss.

Having been on track to fly through A-levels, she’s now reduced to volunteering a few hours a week in a food bank.

‘I wanted to be a doctor, I was on track to get A* for everything,’ she says. ‘According to my medical record I showed only a mild improvement in mood with the ECT but they decided to keep going. I was complaining of memory issues and their response was to step up the ECT dose.

‘It’s just too upsetting to talk about what’s been taken away from me. I feel I haven’t got much chance of anything any more.’

The only information leaflet praised by Professor Read was produced by Mind, which had no inaccurate statements. Mind has joined Professor Read in calling for a comprehensive government review of the use of the therapy.

‘We know some people have found it effective for improving symptoms of mental health problems — particularly depression — when nothing else has worked,’ Mind spokesperson, Stephen Buckley, told Good Health.

‘However, we still don’t know why it works or how effective it is. Some people who have had ECT may have found they experience adverse side-effects that are worse than the symptoms of the problem they’re trying to treat.

‘It’s vital that a range of treatment options are offered and any side-effects are explained properly. The decision to use ECT should never be taken lightly.’

The Royal College of Psychiatrists said: ‘Our guidance is evidence-based, information and developed with input from those who have received ECT.’